About Jo

The Unfinished Journey—The Life and Art of Jo Hsieh

Written by Xiaoxi Lin and translated by William Rogers

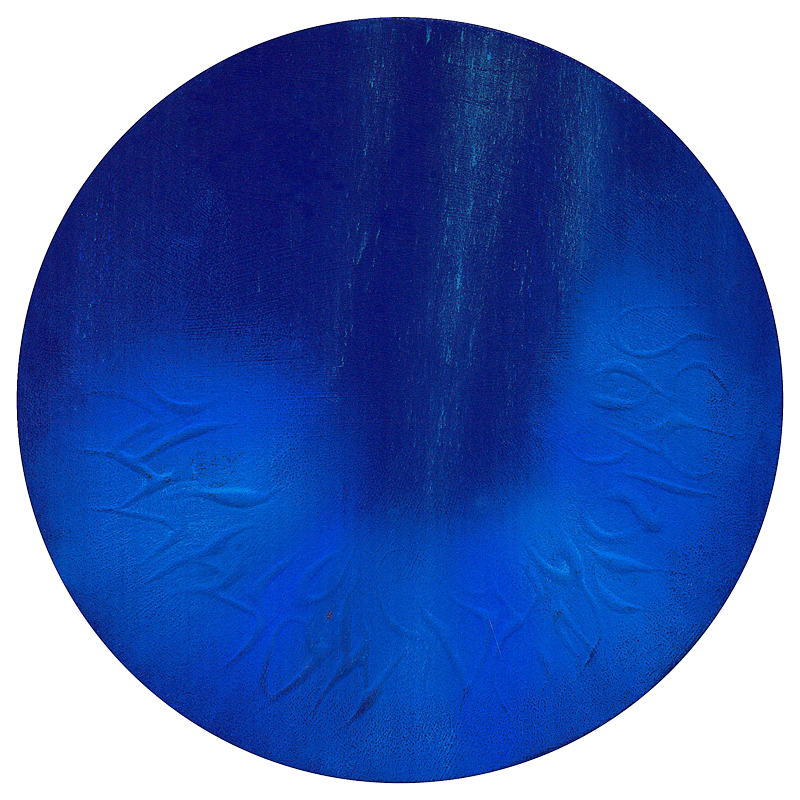

JO Hsieh,None-Space P36,30cm,Pigment and Polyacrylate on Canvas,2013

Blue is the color that was central to Jo Hsieh, a blue that grips its viewers with tremendous force. To begin to understand that Blue one needs to understand her life--her creative journey and the sweetness and the bitterness that accompanied her on that journey.

CHILDHOOD: Jo Hsieh was born with an Attitude—“I’m Not Going Your Way. I’ll go my own way.”

She was born in Chiayi, Taiwan, in 1967, the youngest “little sister” in her family, joining two sisters and a brother. But she was an unexpected and, at that time, unwanted child. Her parents were school teachers who lived in a dormitory with their children, and their income could hardly support the three children they had. Best would be to give away this unwanted child, they thought.

But fate intervened. As they were bicycling to the hospital for the birth, their little boy slipped off the bicycle and fell on the road. He was ok, but his parents found themselves sidetracked and put aside the idea of giving away the coming child. Jo would join the family!

A family elder glanced at the newborn daughter and said, “This child will either grow up to be a dragon or a worm!”—which meant that this unwanted child would be a headache for her parents and siblings. That would prove to be true, but the unique qualities of this child would lead her to extraordinary achievements in art.

From the time when she started jumping and running about, she was different from other children. Her parents had been able to buy a single-story house with a courtyard in downtown Chiayi that had a creek on one side and rice fields on the other. This allowed her to run even more wildly! Every time the neighborhood kids went out to play she refused to walk on the ridge in the fields; her preference was the wobbly edge of the ditch. When her sisters cautioned her about it, she would respond forthrightly in her dainty yet determined voice: “I’m not going your way! I’m going my own way!”

The fact is that she wasn’t interested in playing with her siblings. She’d say they were too dull, and she would rather be alone in her world or pay a visit to the old veterans in the neighborhood. Was this unusual little girl born with an old soul or was going against the current something written in her blood?

Typical of the young Jo was once when she was not yet old enough to begin school and had just learned how to bike. She got into a fight with her brother. Angry, she then biked a dozen kilometers to the school where her mom worked to tell on him. The teachers she saw laughed, and she became known as an “admirable little sister,” always ready to defend her rights. Yes, one could call her an “old soul” or simply unconventional, but this much is sure: her stubbornness and strong will meant that she would hold her own and stick with her sense of right and wrong despite what anyone else or any group thought.

But, one could ask, where would this strong individualist fit in? She certainly had a difficult time fitting into Taiwan’s educational system, one that called for “cramming” information while discouraging dialogue. Her playful and often cynical attitude had her teachers running in circles. While not being afraid to voice her opinions, always asking “Why?” would lead to warnings, demerits, and her parents being called to school. But she never wavered. For other kids of the same age , she had a commanding charisma; names like “big sis,” “delinquent,” and “dunce class” followed her wherever she went.

Sometimes her parents, driven to extreme frustration by her actions, would say, “Why on earth are you behaving this way?” And she would sigh and reply, “You wouldn’t understand.”

Was she a “bad kid”? Maybe from the point of view of the adults around her, but in fact she only needed to find a welcoming, encouraging environment. With that she could go forward. In due course, she found that Art would be her way forward.

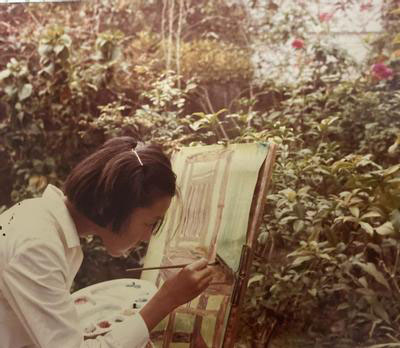

Young Jo painting in her backyard.

When did Art come into Jo’s life? Very early indeed, because her mother was aesthetically inclined in many ways. In fact, she opened a weekend children’s art studio in their home as a way of augmenting her income as a school teacher. Jo always participated—and loved every moment of the experience.

But her future path was unclear since she had no interest in what was taught in school and rejected the “structured learning” that went with it. She did manage to make it through junior high school, but where to go from there? Further education was out of the picture. At this point her father stepped in and offered Jo two options. One was basketball (since Jo was tall) and the other was the Fu-Hsin Trade and Art School in Taipei. Jo chose Trade and Art!

Even though she remained in the educational system that she abhorred, at least she had art as a creative outlet. She went on being the “Big Sis” and “the delinquent” who continued to receive warnings and demerits. Her sister, who lived in Taipei and took on a paternal role, was called again and again. But Jo, full of energy, devoted herself to painting. And, somehow, she managed to graduate from Fu-Hsin and even quickly landed a job with an advertising design company.

Young, headstrong, and brimming with talent, she was eager to make something of herself. In her early 20s she started her career with the fierce dedication of the “Big Sis” that she was. She strutted with such confidence and lack of fear that she gave the impression that she’d been in the company for years. She soon surpassed her peers.

Although she faced obstacles and hardships, her remarkable resilience made her able to fight the fights that had had to be fought. And won.

However, she soon discovered that Design (done for “the market”) and Art (done for the self) are very different endeavors. She could have continued, but her longing to be a free soul, creating what she wished, not what others wanted, was very strong. After a few battles with herself, she brought this jarring news to her family: “I’m going to study abroad in England!”

Her conservative parents knew the kind of young person Jo was, but they’d never imagined hearing “study abroad” from one of their children—especially the “little one” who had been nothing but trouble in school. But they also knew better than anyone else that once Jo Hsieh had set her heart on doing something, no matter how unusual or rule-breaking, there was nothing that could sway her from that. So it was that in 1991, when Jo was 24 years old, she flew off to London, alone on a journey she was never to regret.

Jo always has her unique dressing styles.

Jo’s Years in England—Living in Non-Space Everyday

In England while Jo was busy fitting in, studying, painting, and making friends, she still made time to write twice a week to her beloved family. Her A4-sized letters were filled with details about people she had met in school, which teacher’s lessons she enjoyed most, what attractive coats she saw on sale in the mall (since she knew her mother loved stylish clothes), and complaints about how her undergarments never fully dried in England’s cold and rainy weather. She would write lists of things she needed—with willful demands to “Buy these! And send them to me ASAP!!!” (Exclamation points, many of them, were common in her letters!) She made it a habit to send two letters a week for a year until her classwork began taking more of her time. Then she wrote less often. But those letters had keen observations on everything and everyone she encountered. It was as if even the least significant event was worth experiencing with heightened awareness.

When she applied that “awareness” to her art, impelled by a particular professor, the result was dramatic:

“In my four years in Fu-Hsin, I didn’t know what Art was. . . . I came to England in 1991, and initially not much happened. . . . I made myself paint every single day and felt drained. But entering the Chelsea College of Arts in 1992 had a great impact. Of particular importance was the influence and encouragement of one professor, Amanda. She was the one who named my research subject Non-Space. During the three years I spent in Chelsea, I lived inside my Non-Space every day. Now in 1996 I’m in the Royal College, and I’m going to thoroughly document every facet and aspect of Non-Space!”

So it was that with Jo’s resolution to take charge of herself and with the assistance of the liberal education in the arts that England offered the once willful, angry, and cynical young woman from Taiwan “changed into another person,” as her brother said. She immersed herself in paint and paper every day, finding there what she had needed even in girlhood: the acceptance and the encouragement that would allow her innermost self to be expressed. “I was happy every day because I was in the free, open, and liberal environment I had always yearned for.” This was especially the case when she was with her mentor Amanda, whose sympathetic presence allowed Jo to talk about anything and everything. Jo’s entry into Non-Space took place as soon as her second year in England.

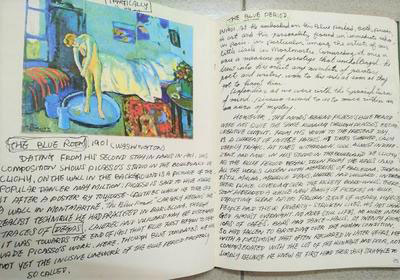

Her book is always full of notes.

The Essence of Non-Space—An exercise reaching into the Psyche

In her writings about Non-Space Jo brought together many disciplines and beliefs, including physics, philosophy, psychology, Confucianism, and Taoism. She was also well aware of art history. But the essence of Non-Space can be expressed in simple words: as opposed to visible and tangible space, there exists an unseen and intangible space. It does not exist in any neatly-ordered time sequence accessible to humans, but in a state of chaos. This ever-borderless and boundless Non-Space was, in fact, the vast cosmic and emotional world that existed in Jo Hsieh’s mind.

She presented Non-Space to everyone through the only physical, tangible means available—which was ART, a way of reaching into the psyche. And the kind of art that Jo created was one of abstraction.

Even though the phrase “abstract art” has often been used to refer to Jo’s art, what she painted, however “abstract,” was a realistic and figurative representation of what was in her mind—a mind rich and complex. She once said, “Painting understood what I wanted to say when no one else did. . . . I’m the saddest when I’m painting, but also the happiest. . . . Painting is my best friend.”

Jo Hsieh poured herself and her art entirely into Non-Space. Her profundity was Non-Space’s profundity. Truly, Jo and Non-Space became one and the same.

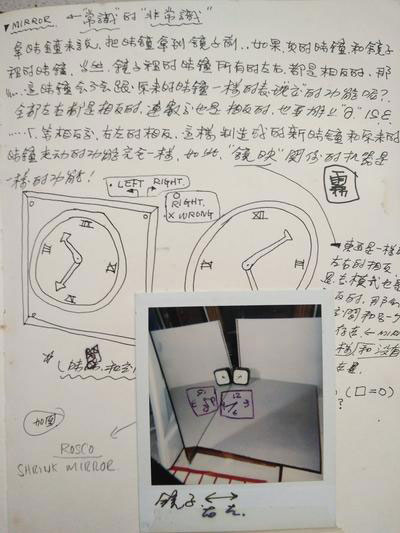

She wrote down all the None-space related theories in her notebooks.

The Manifestation of NON-SPACE—a Higher Spiritualism

To a superficial observer of Jo Hsieh, she might have appeared to be just another art-loving maverick, going it alone, making it up as she moved along, but in fact, she spent half of her strenuous (and all too brief life) becoming a humble and ever loyal disciple. When she talked about her art she never hesitated to name the many artists she was inspired by.

When she mentioned Yves Klein, who is famed for his handling of the color blue, she emphasized his persistence in pursuing art; when she referred to Henri Matisse, she dwelled on his freedom and lack of homage to the traditional. In the case of Pablo Picasso, she empathized with his subversive aspiration for liberation. When she mentioned Monet, she emphasized his desire to create art despite the fear of blindness. As she wrote, “The Impressionists too struggled for decades . . . . All forms of perseverance are essentially [wrapped in] solitude.” She knew the art history of Europe and recognized that her path of being free to follow her own path was one that had been followed by her great predecessors—artists who often struggled alone, defying the artistic conventions of their times, facing and overcoming denigration and rejection.

The Taiwanese girl that no one seemed to understand realized all of this. She would have to pursue her own vision of art regardless of the toll it exacted. Art had a sacred and inviolable status for her. The inner spirit of Non-Space meant more to her than any effort to give it material form. Art was the sublime conviction that guided her life.

Even though her conception of art was hers alone, without overt efforts to gain an audience, the first exhibition of her art in England was a great success, with 80% of her creations sold. Even Prince Charles was enthralled by her Blue, and she was even called the “Royal College of Art Lady.” But, so typical of her, she couldn’t have cared less about her success in the art market and the publicity that it engendered. She told her brother with genuine disappointment that “they didn’t understand me, they only liked my blue.”

Was she “conceited”? But weren’t the artists she admired also “conceited” in that they broke, often radically, with the traditional art of their times? One might say of Jo Hsieh that she was, from the beginning of her life to the end, a proud angel with clipped wings who found herself having to live with mortals who could not see or comprehend the profound world beyond the mundane world of day-to-day life.

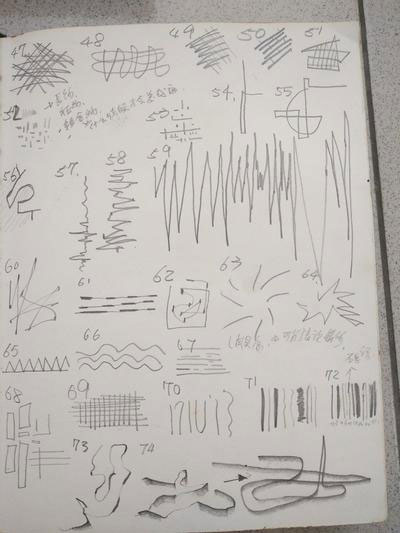

Jo drew hundreds of lines to represent different kinds of emotions.

Non-Space Represented—Point and Line to Plane and Blue

Behind the process of giving form to Non-Space were Jo Hsieh’s rational and even scientific experiments. It was through repeated comparisons, examinations, and meditated decisions that every piece of her Non-Space art arrived at completion.

The development of Non-Space can be divided into two periods. The first was “Free Abstraction,” which extended from 1992 to 1996. Jo Hsieh took the concept of Abstract Art as it had developed in Western art history and combined it with her own engagement with Eastern philosophy. This emphasized sensual and abstract states that grew out of “Musicality” and “Point and Line to Plane.”

What she wrote about art makes this clear:

--“Point, it’s the beginning and end of all.”

--"My understanding of Wassily Kandinsky’s definition of a point is that it is an emergent phenomenon, the prototype of movement. Just as extremes meet, the state of absolute stasis is the initiation of movement, the emergence of action . . . . The movement of stasis is not an actual movement, but an inner spirit. . . . The movement of action begins with objective activity.”

--“Do you hear the line? Do you see the music?”

--“Movement of a point forms a line. Movement of a line—like sideways chalk—forms a plane.”

--“What do my emotions look like? What can I use to help me express them?” “Line.”

--“With a Plane, overlapping is another form of spatial expression besides size . . . . Overlapping is essential in Chinese ink painting, especially so for the spatial relations between mountains and clouds. The substantiality of a mountain is expressed through the overlapping of textured stroke patterns. . . . Overlapping produces space out of which comes distance, and out of distance, and from distance, remoteness. And from remoteness, the span of time.”

When Jo Hsieh asked herself, “What do my emotions look like? What can I use to help me express them?” Her answer was “Line.” She went on to make hundreds of sets of lines to explore and dissect all kinds of emotions.

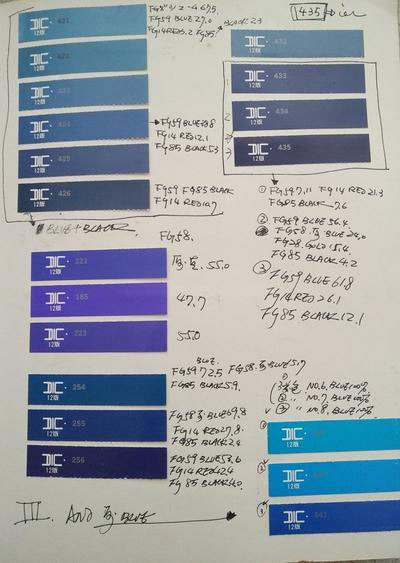

It took Jo many tries to find the BLUE that represents her None-Space.

Her second period beginning in 1997 was the “Blue Period,” which entailed entering into a deeper dimension of Non-Space. She had an intuitive love for the color blue, which she described as “very stable. It’s a very philosophical color.” This she also linked with the most mundane substance on our planet—water. Ordinary as it is, for Jo Hsieh it was “a most mysterious and extraordinary thing. It exists in very different forms: solid, liquid, and gas. We humans could not exist without it.” So it was that in her Blue Period while developing the concept of Non-Space, she collected not only different shades but also differently textured blues. A crucial aspect of Jo Hsieh’s Non-Space art was the blue mineral pigment lapis lazuli.

Non-Space in Jo Hsieh’s own words

--“I have a personal and deep affection for the color blue. It always seems to speak to me, so mysterious and incredible it is; translucent yet profound. . . . It is like being enveloped in the voice of Maria Callas singing opera—so close and so distant at the same time.”

--“Blue is serene, without harshness, and possesses a stance of rationality, mental stability, a balance of body and mind.”

--“You can feel Non-Space with every part of yourself—body, eyes, hands, heart, and truly your whole self. Every fulfilled person has an esoteric connection to this mysterious space.”

--“The blue pigment is so primitive and pure, so deep and lucid. It beckons to the Non-Space deep within one’s heart.”

--“If we possess the ability to see through our Non-Self, we can perceive the true essence of all things inclusively and thoroughly, and realize that nothing in this world is out of the ordinary. There won’t be any need for obsession or infatuation. We will become unwavering in the face of everything. Only when our minds are free of the obsession of ‘Self’ or even of all obsession will it reach a state clear and serene.”

--“In Psychology, the world of the unconscious is considered to be free, pure and primitive, while the mental condition of the conscious mind is often suppressed. Only the activities of the unconscious mind are closest to the true self. My only wish for Jo Hsieh—within Non-Space—is to freely develop without fear. The unconscious is transparent, soft, and reflective!”

OUTSIDE OF NON-SPACE—The Polymorphic Jo Hsieh

A fascinating fact about Jo Hsieh is her variability. In her short life, she took every fleeting moment of time—however trivial it might seem to others—and expressed it to the world through her art. It was not uncommon for one of her art projects to take hundreds and thousands of pieces to develop. This is particularly the case with her self-portraits, some having over 1600 pieces. (And one must forget her lovely and comical “Cats Series.”)

A LIFE CUT SHORT—Much Work Done, Much More Work That Might Have Been Done. Jo Hsieh’s Homecoming to Taiwan

Jo Hsieh had an intergenerational friendship in England with her landlord, John, a serious British gentleman. They didn’t get along right away, but that changed when John became aware of her dedication to art. A sign of this was that the light in her window, day and night, never went off. He was so moved by the devotion of this young Taiwanese woman that he would often check on her to make sure that she was taking care of herself.

John’s concern was well founded since Jo Hsieh would lock herself in her studio and work day and night—a commitment that eventually affected her health. Feelings of depression led to deep fatigue and headaches. However, even when her hands started shaking involuntarily, she kept on painting.

On Christmas Eve 2014 John discovered that Jo Hsieh had passed out in her apartment. Taken to a hospital, she was found to have a brain tumor. She had been in England for twenty years and had always hoped that her homecoming would be triumphant—not for herself, but for her loving and supportive family. At the beginning of 2015, her devoted brother flew to England and accompanied her on a return flight to Taiwan.

She died in 2017, in her 50th year, having spent her final years with her beloved family.

In considering the art history of Europe, we find that some of the innovators and now-recognized geniuses were in their own times outsiders who had to wait many years before their accomplishments were acclaimed as those of a master, of a genius, of one of the greats. Among these artists was certainly Jo Hsieh, who left her native land and, fulfilling her artistic destiny, lived in England for many years. (Here we should recognize that women artists in Europe were often neglected.)

Although her untimely passing filled the hearts of many beyond her ever-devoted family with a sense of great loss, Jo Hsieh will be remembered as a gleaming star, giving of herself to open new vistas in art. Her oeuvre will continue to shine long after her passing, speaking of her total commitment to art and to new dimensions in art. In this sense, Jo Hsieh is still with us.

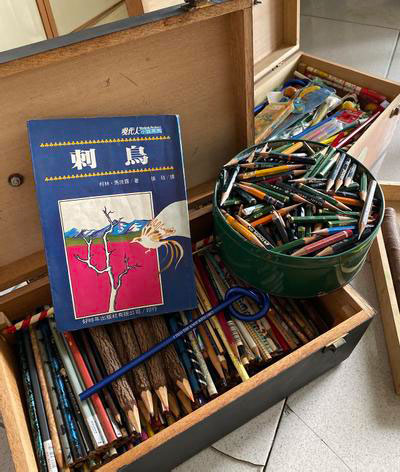

Jo collected all kinds of pencils and all the pencils she used.

Epilogue

As the writer of this commemoration of the artist Jo Hsieh, I would like to express my gratitude to Jo Hsieh’s family for their support and for the many insights about their beloved Jo that they so freely expressed to me.

Jo’s devoted brother told me when we met to talk about her that she had a hobby of collecting pencils. He then proceeded to open box after box of pencils. I was amazed by the number and variety of these pencils, but what caught my eye even more was a cylindrical metal box full of pencil stubs. About them Jo Hsieh told her brother, “These pencils are my memories, they’re my thousand days in London.” Her family and friends all knew that what truly lay in the box were her diligence and persistence. Her brother also told me that every time he visited her in London, he would wake up in the middle of the night and, seeing her still at work, make her stop painting and go to bed.

As our conversation went on, he grabbed a book and said, “This is my sister!”

This is the passage in the book he was referring to:

“There is a legend about a bird which sings just once in its life, more sweetly than any other creature on the face of the earth. From the moment it leaves the nest it searches for a thorn tree, and does not rest until it has found one. Then, singing among the savage branches, it impales itself upon the longest, sharpest spine. And, dying, it rises above its own agony to out-carol the lark and the nightingale. One superlative song, existence the price. But the whole world stills to listen, and God in His Heaven smiles. For the best is only bought at the cost of great pain.” (From Colleen McCullough, THE THORN BIRDS.)