News

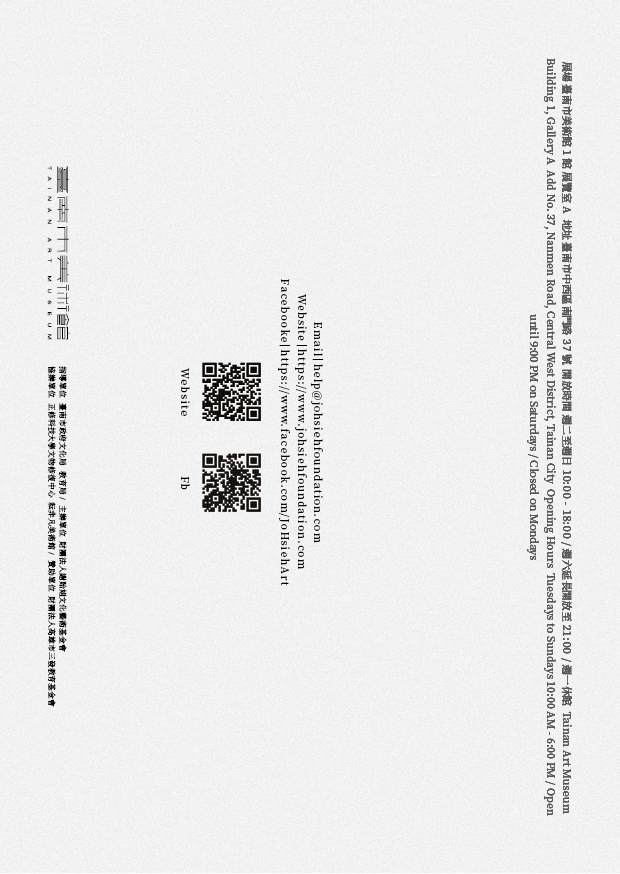

A Philosophy of Blue: A Retrospective of Jo Hsieh|2023/10/14-2023/11/13

A Philosophy of Blue: A Retrospective of Jo Hsieh|2023/10/14-2023/11/13

Location|Tainan Art Museum Building 1, Gallery A

Address|No. 37, Nanmen Road, Central West District, Tainan City

OP Hours|Tuesdays to Sundays 10:00 AM - 6:00 PM / Open until 9:00 PM on Saturdays / Closed on Mondays

Curator |Professor Kuang-Yi Chen

SEMINAR

2023.10.14日(SAT) 13:00-14:30|Tainan Art Museum Building 1 導覽室

OPENING

2023.10.14日(SAT) 15:00|Tainan Art Museum Building 1, Gallery A+Workshop Room

The Philosophy of Blue – 2023 Jo Hsieh Retrospective Solo Exhibition

By Chen, Kuang-Yi, Professor in the Department of Fine Arts at National Taiwan University of Arts

After the death of the Taiwanese-born, British-residing artist Jo Hsieh, her family set up the Jo Hsieh Arts Foundation to preserve and advocate for her art and literary works. The foundation’s first exhibition will be held at the Tainan Art Museum this year (2023) — and this will also be the first time her works are exhibited at an art museum. The exhibition features two of Hsieh’s art series: the Blue Powder Pigment Painting series she is known for, and the lesser-known and under-studied Self-Portrait series.

Starting in 1997, Hsieh devoted 20 years of her less than 30-year career as an artist to the study of blue. A sketchbook Hsieh left contains much of her research into the color blue. Of course, such research can be conducted with any color, but she always stressed how unique the color blue was to her: “I have a strong personal preference towards blue. I can feel that it speaks to me and is mysterious, incredible, see-through yet distant..." Hsieh also referred to blue as the color of philosophy and even considered blue as the fundamental color in her thought process. Such an understanding of and preference for blue is what compelled her to create monochrome blue paintings after she settled in the UK, and this is the Powder Pigment series of her None-Space collection.

Hsieh created this unique style through a complicated process. On a canvas covered in blue acrylic base paint, she would first create subtle, mysteriously supernatural protrusions shaped like Sanskrit or waves. She would then smear a “special pigment mix” containing a variety of blue colorants onto the canvas by hand. These square, rectangular, and circular monochrome shapes with otherworldly summoning power are each as vast as the universe and as small as a ping-pong ball, emitting indescribable lights in spaces where they are hung.

The reason why Hsieh and countless artists from all times and all around the world become so obsessed with blue and using it as the core of their creations, is because this color has a unique position in art history. In ancient times and the Middle Ages, blue was the rarest and most expensive color, and it wasn’t until after the arrival of industrialization that blue became ubiquitous. Hsieh used multiple shades of blue, researching materials to create her signature blue by mixing pigments such as ultramarine blue, Prussian blue, navy blue, and cobalt blue.

Yves Klein (1928-1962), an artist who influenced Hsieh profoundly and the creator of International Klein Blue (IKB), believed that ultramarine blue is the greatest iteration of blue. Klein declared that "blue has no dimension, it is out of dimension…all the colors bring associations of concrete ideas. Whereas the blue recalls at most the sea and the sky, what there is of more abstract in the tangible and visible nature.” Klein’s depiction of blue being without dimension, empty, abstract, and immaterial is very close to Jo Hsieh’s concept of "non-space." Hsieh always believed in the existence of non-space, which she said is "immaterial, just like air" and "has neither beginning nor end." And such a space obviously does not exist in the tangible world; rather, it points to a spiritual place that exists in our soul or imagination.

It is also worth mentioning that both Klein and Hsieh preferred using pure-color pigment to create monochrome paintings. Retaining pigments in their powder state was essential to liberating their paintings. This unique method of creation highlights the purity and the immaterial materiality in painting. Only when material is liberated can one be immersed in the complete, pure, and free "non-space," and blue is the key used to enter this space.

Furthermore, Hsieh manipulated color fields in different shapes and sizes with a mixture of various shades of pigment to create an illusion of light, shadow, and depth. Her skilful manipulation allows blue to fully unleash its power that expands the space endlessly and infiltrates the viewer's sense and consciousness, bringing the peace of mind, vastness, and depth of the spiritual realm — and even the awareness of time and timelessness. So the existence of Hsieh’s "non-space" depends on the viewer’s spirituality and sensibility.

Self-Portrait, one of Hsieh’s lesser-known series, is done in a unique genre of portrait painting that became extremely popular after industrialization in the 19th century. According to Hsieh’s family, she produced her earliest self-portrait in 1992, but it wasn’t until September 15, 1993, that Hsieh started her project of creating one self-portrait a day on A4 paper (30.4 cm x 22.8 cm) until July 19, 1999. The total number of her existing self-portraits, as counted by her family, stands at 1,619 as some went missing.

Hsieh used these works to experiment freely with all kinds of techniques, styles, and mediums, and presented an astonishing diversity in form that covered almost all possibilities in art. Hsieh used a mixture of mediums, such as oil, watercolor, ink, and pencil, and tried all kinds of styles. In addition to regular portrait practices, some of the self-portraits are related to her blue series, some are extremely minimal to nearly nothingness, severely distorted, graffiti-like, and barely recognizable under frenetic and dynamic brushstrokes of abstract expressionism. Others are weird and funny, or rendered in comic-book style with facial expressions containing all kinds of emotions, including happiness, anger, sorrow, and joy. She even produced a series of self-portraits in sculpture form, photographed them, and collaged the photos into a face-like pattern to challenge herself in creating a pareidolia effect.

Along with the faces, the excessive presence of her hands — either resting on her cheeks, holding her forehead, caressing her face, covering her face or mouth, propping up her chin, or holding a cigarette — also plays a specific role in these self-portraits. With the addition of these suggestive gestures, the faces in Hsieh’s self-portraits connect with the viewer through emotions such as annoyance, pain, anxiety, surprise, frustration, and distrust. Hsieh also produced many portraits of herself with her cats.

It is difficult to interpret Hsieh’s self-portraits, but the phenomenon of artists painting a large number of self-portraits is related to “solipsism,” especially works that obviously combine symbolism and expressionism. Self (soi) is undoubtedly an expression of consciousness, which is also the only verifiable existence relative to the external world. The most striking piece in Hsieh’s collection is Self-Portrait 0012, which features a skull on the back that symbolizes death. The self-enquiry into one’s own existence and essence of life prompted her to paint herself on a daily basis. Although she stopped producing these self-portraits in 1999, she still strives to produce a gigantic piece work called Life.